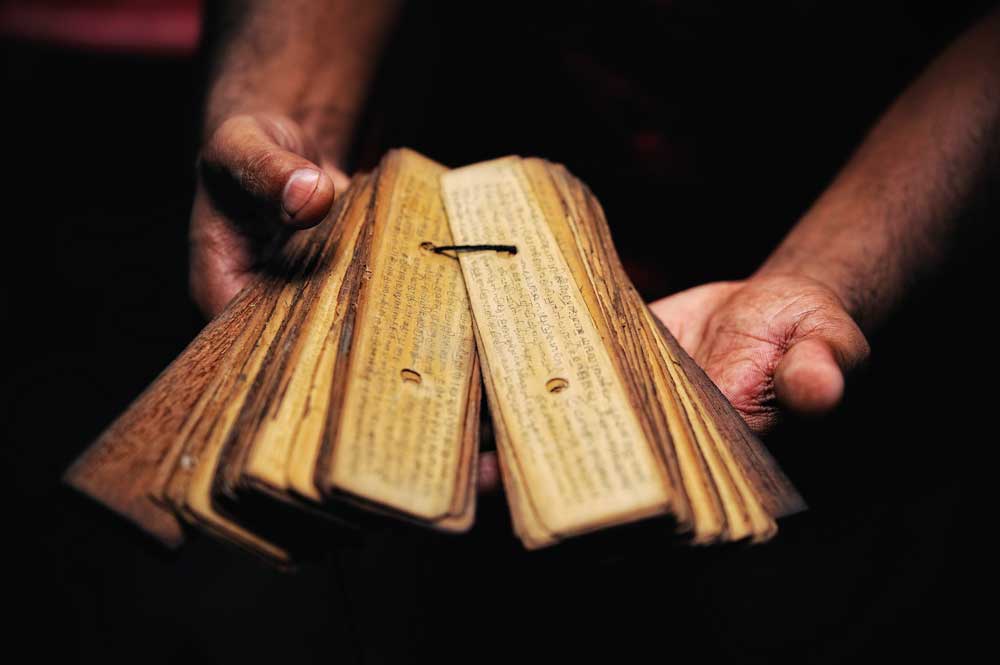

“The Buddhist Notebook is a new series of writings from and about Buddhist philosophy. From the jataka tales – moral and philosophical fables from the Pali canon, to reflections on the life and teachings of Lord Buddha, the notebook is a passion project helmed by our co-founder and CEO Isabella Arensen. Each week, a new story or short essay will appear, and these writings will be collected and published as a book: The Buddhist Notebook. The first entry in this notebook is a translation of a jataka tale: a story about leadership, and a reflection on what it means to lead with empathy and a clear mind.”

The quails in a forest came to hear about a man stalking the woods in search of birds and game. Of course, there was nothing unusual in this; but this man happened to be clever, and the quail began living in fear of that clever man and his net. The man was known all over as a trickster- someone capable of throwing his voice in unexpected ways. To catch a quail, he found, all he needed was to play at being one. So, he learned how to call out like a quail caught in a trap, crying out for rescue. The moment other quails heard these cries, they flocked out of the undergrowth, ready to do every possible thing to save their fellow quail. Noble, the hunter thought, but ultimately stupid. All these noble quails ended their days in his nets; then in his baskets; then in market stalls and cooking pots.

The king of a thousand quails made a careful study of this hunter, his tricks, and the changes that had come over the forest, all on account of one clever man and his net. This was a respected quail-king, wise and cautious, forever looking out for his flock. Seeing that the clever hunter was drawing closer to their corner of the woods, the quail-king gathered his flock and made his feelings known; and the quail-nation listened intently. The thousand quails welcomed strangers, too: other quails from flocks all over the forest. Once they were settled, the quail-king said clearly,

“There is a hunter in these woods, trapping us with tricks. Every quail-nation is in danger of being caught, killed and eaten. I understand, I think, how to save all our lives. The hunter will come- we can’t stop him. When he does, and when we’ve had his nets thrown over us all, every last one of us must sit up and crane our necks as high as they will go. This will allow us to take flight, and his net? We’ll drop it over a waterway, in the canopies of a tree. Wherever we like. But first, every last one of us must lift our heads and beat our wings. Only this will allow us to escape.”

Not one single quail objected: their king was a wise leader, always watching out for the safety of all flocks, not only his own.

As expected, the hunter came. His nets were dropped over the birds; but as they craned their necks, took flight and carried the nets away, letting them fall over the nearest river, the hunter realized that he had met his match in this part of the forest. He had made his quail-call and trapped the birds, he thought. The clever hunter had been outsmarted by his prey, and he had to chase his nets downriver. When his wife discovered that he had met his match in a flock of birds, she tormented him relentlessly, nagging and badgering him until his patience burned out. In the end, he said to her,

“Listen: people fight and try one another’s patience. These birds are so clever, and eventually, they’ll start fighting amongst themselves. When the infighting starts, they will be divided, and I’ll have my way with them. Just wait. You’ll see I’m right.”

The hunter’s wife refused to back down, and the hunter endured several weeks’ worth of shouting and complaining each time he returned with empty hands and no nets.

One day, among the many quail flocks that had gathered for the protection of a much larger group, one quail stepped on the tail of another quail. He apologized, of course- as politely as possible. But the quail who’d been stepped on was not ready to let it go: in no time at all, they were chasing one another in circles, shrieking at one another, pulling feathers, and their fighting rippled through the rest of the flock. The quail-king was alerted to all this noise, and he flew over to see it for himself. One look told him that these birds, who were not members of his flock of a thousand, would go on warring with one another and put every last quail in danger when the hunter made his next approach. Although it saddened him, he knew what needed to be done. His own flock had to leave the larger gathering for their own good; and on the wise king’s command, they flew away.

The warring quails fought so vigorously and so loudly that they barely noticed the arrival of the hunter, and as the clever man cast his nets, the quails went on fighting. They knew how to save their own lives and those of every other quail caught in the net: all they needed to do was to lift their heads and beat their wings. For some reason, they refused.

“Why would I hold up my neck and beat my wings to save you?” One said to the others. “Why should I lift a neck or a wing for anyone else? What’s in it for me?”

So, the quails fought on and on; and the hunter was able to net them all. He hauled the birds away, first to the market, where many were killed and sold. The rest, he took home to his wife. The nagging came to a welcome end: the hunter’s happy wife killed the remaining birds and made them the pride of a feast she cooked for their family and their neighbours.

Deep in the heart of the forest, the wise quail-king heard all this with great sadness. He was heard to murmur to himself, we worked together for and with one another, and we were safe from the hunter and his nets. Then we chased one another around and around, snipping out one another’s feathers, blind to the danger all around us. That’s how you end up in a real fix: from the net, into the cooking pot, from the forest, right into the fire.

Translation and retelling © Isabella Arensen 2020